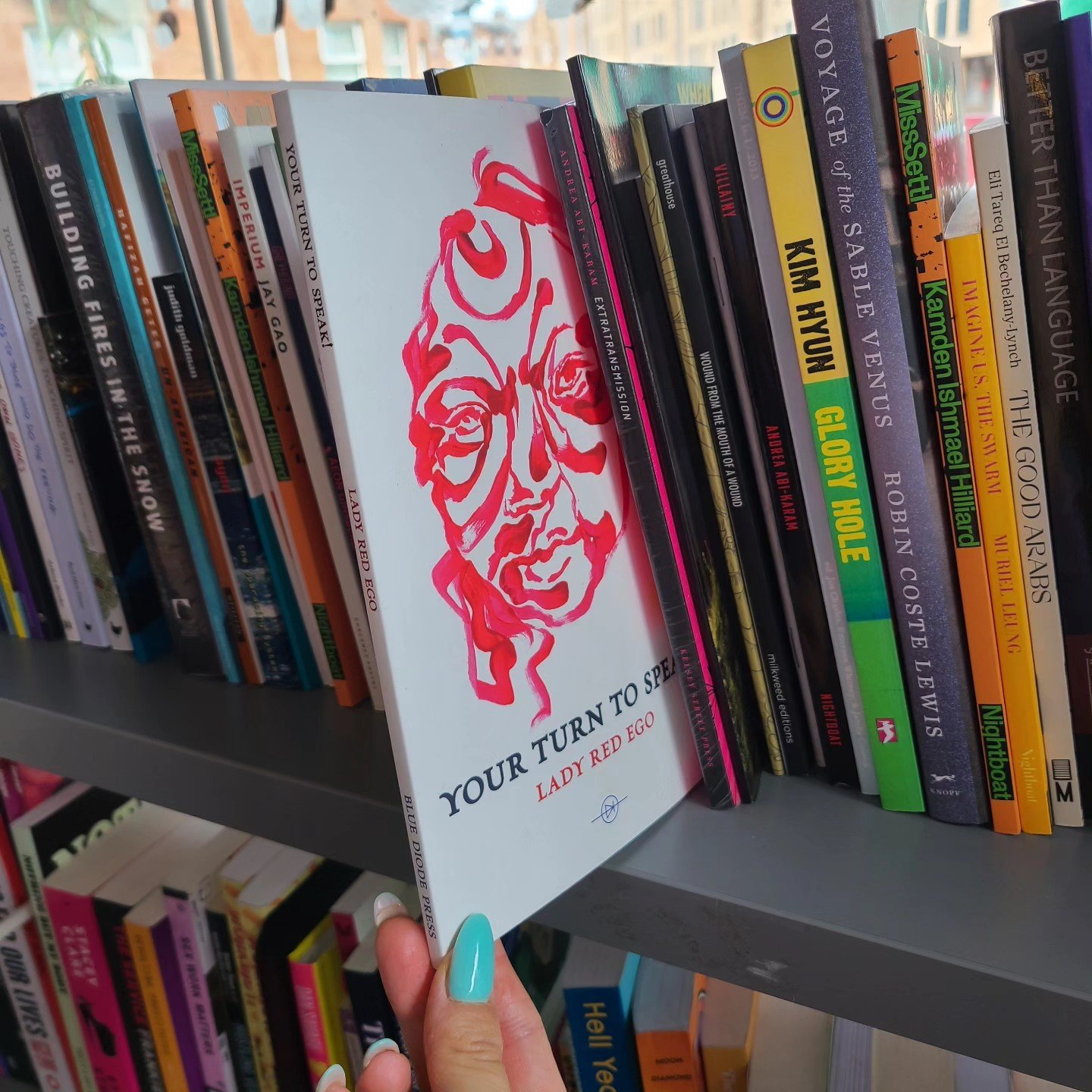

Lady Red Ego on Voice, Monstrosity, and Intersectionality in Your Turn to Speak!

Lady Red Ego’s Your Turn to Speak

I’m drawn to voice. Since the publication of this collection, many people have asked me why I chose to work with Greek mythology, but it comes less from a fascination with Ancient Greece, and more from how Greek mythology has been built upon throughout Western literary culture. It’s a tapestry of translation that has become its own breathing and living creature. I wanted to slice into the density of that fabric.

I think the interest in voice shows in many of my previous works – The Red Ego, my first pamphlet was about crafting a new voice to play with, and my pseudonym, Lady Red Ego, was captured from that collection. My published name is a character in her own right. My second pamphlet, Natural Sugars, takes from Shakespeare’s Queer Pastoral Ecology – a term I’m borrowing to refer to the forests in A Midsummer Night’s Dream and As You Like It. Your Turn to Speak was a natural elevation to an even bigger stage – that of gods.

I started writing the main body of this work in my last year of university for my creative dissertation. The original pieces involved famous characters within literary canon from all sorts of time periods and places

I wrote a few about Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West, for example. But because I took a classics course in high school, I already had a built-in knowledge of Greek mythology, so their voices came to me rapidly. And there was, of course, a timeless grandiosity to them, which was very sexy. I like sexy poems. (I think everyone who has read my work knows I like sexy poems.)

I wrote a dissertation proposal for the main body, which became the first act of the book. But the third act, I wrote after graduating. In a way, it’s my favourite act. There was a character in the first act and third act, Polyphemus, who really stuck with me. One of my biggest influences, Anne Carson, wrote An Autobiography of Red, in which the Greek Monster Geryon is rewritten into a young man as he lives out his first heartbreak.

Monstrosity intrigues me. I read an article when I was studying about Frankenstein being a racial caricature of 19th century Britain. An English teacher of mine once said something about how monsters are nothing more than realisations of society’s prejudices and fears. As a woman of colour, I’m very aware of the way my own body is read and the various oppressive gazes that are imprinted upon it.

And I’m aware of how living through these gazes has shaped my behaviours and emotional responses. A monster is created when an oppressive narrative has naturalised itself – when there is only one truth. The potential for victimhood is removed because monsters are often stronger than the hero. Their physical prowess is their Achilles heel. Should they utilise whatever strength they have, it will only serve to define their monstrosity further. And if they do not, their silence becomes a kind of monstrosity, too.

“Monstrosity intrigues me. I read an article when I was studying about Frankenstein being a racial caricature of 19th century Britain. An English teacher of mine once said something about how monsters are nothing more than realisations of society’s prejudices and fears.”

When I wrote Polyphemus, I discovered how noble he felt to me. The island upon which Odysseus discovered him was his. He was indigenous to it, like Caliban in The Tempest. In the first act, I felt his rage. But in the third act, I felt how lost he was – how it feels to be overpowered by the narrative, and how, after being overpowered for so long, it feels to come into that power. I realised that coming into that power wasn’t always triumphant, but rather incredulous. What can you say, after being silenced for so long, that can possibly encapsulate those centuries of silence?

Ithaca’s poem is about eating your own tail. The narrative circles in on itself, seeking a direction, or an identity, after finally being released from its cage of silence. The land asks questions it knows the people on it cannot answer. The paradox of monstrosity – and by extension, diaspora writing – is at the heart of it. The English language, the very medium used in the work to reclaim narrative power, is a colonial language. English is my first language, and I have so much tenderness towards it, but I am also very aware of how it refutes every attempt I make to hold it accountable. It devours every betrayal. The last line, “He cannot say it” is in part about what I cannot say, what I cannot expect my readers to receive.

Lady Red Ego reading from Your Turn to Speak at an event at Lighthouse Bookshop

On a personal level, I owe a lot to the English language. It has given me the means to be heard. But I know that, as someone with intersectional identities, it has also led me to be tokenised in the Scottish poetry community. When you are recognised as a queer and BIPOC writer, there is the anticipation of a certain kind of revolt within your work and how it interacts with the canon. Even revolt is commodified. But I don’t think my work is revolutionary, nor is it representative. It is just as much a product of my own privileges as it is of my marginalisation. I think sometimes there is a simplicity to how non-white poetry is perceived at large – an imagined distillation of justice, poignancy, homesickness and above all, moral courage. But these voices are human voices. They have their own petty agendas distinct to each of them. Even Zeus must ‘want something’. Want, above all, is the force that connects me to voice. The reaching for a place, whether or not you reach it, the endless journeying towards … that is what my writing follows.

Texts Mentioned:

Carson, Anne. Autobiography of Red. Alfred A. Knopf, 1998. ISBN: 0-375-40133-4

Malchow, H. L. “Frankenstein’s Monster and Images of Race in Nineteenth-Century Britain.” Past & Present, no. 139, 1993, pp. 90–130. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/651092.

Nardizzi, Vin. “Shakespeare’s Queer Pastoral Ecology: Alienation around Arden.” Isle: Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment, vol. 23, no. 3, 2016, pp. 564–582. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1093/isle/isw048.